Document Processing In The Time of Artificial Intelligence

In this post we want to explore how modern Large Language Models (some people might call them "AI"), like Google's Gemini, are suddenly capable of processing documents of all kinds, not just text.

According to the official docs of Gemini from 2025-11-12 the API currently supports the following media content

You can either provide this content as a URL, via file upload or smaller files directly inside the payload (<20 MB).

Here, we want to focus on the actual Document Processing capabilities of the API and mainly look into handling of different PDF documents.

PDF Format

Before we can dive deep into the answer to the question how Google's Gemini AI handles document files, we need to discuss what the Portable Document Format (PDF) file format actually is.

Other than text based file formats, like text (.txt), CSV (.csv), TSV (.tsv), JSON (.json), YAML (.yaml) or TOML (.toml) the PDF (.pdf) format is a binary format, simiar to ZIP (.zip or .tar.gz) compressed directories.

PDF is essentially a container that describes a document's layout and content in a way that can be understood by any device that can read the file. This ensures that the document is represented in the same way on any kind of device.

This PDF container contains objects like pages, fonts, images and other metadata, that all get cross-referenced/linked together within a table.

By reading the table and creating relationships between objects we can recreate the document.

Here's an overview of content types we might find inside a PDF file

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Text content | Streams with font references, character codes |

| Vector graphics | Shapes, lines, bezier paths |

| Images | Raster data (JPEG, JPEG2000, CCITT, etc.) |

| Fonts | Embedded or referenced |

| Metadata | Info dict, XMP XML |

| Interactive content | Forms, annotations, links |

| Structure / Tags | Logical document structure for accessibility |

| Embedded attachments | PDFs, images, or arbitrary files |

| Scripts / Actions | JavaScript actions (rare, used in forms) |

Interactive Example

Below you can find an interactive example, that allows you to render your PDF file dynamically.

This is the fun part.

A PDF doesn't store "Hello World" as you see it. It stores instructions on how to draw it.

The text below is a "Content Stream". A content stream is the heart of a page. It's a list of drawing commands in a PostScript-like language.

You can hack around in the textarea and try out different things to understand the format better.

For a more detailed description, check out our interactive Explainer Page!

Please note for demo purposes we only allow you to reference /Img1 or /Img2, otherwise we would need to dynamically create the image object inside the document.

Real life examples

Let's also look into actual real life cases.

Consider these two very similar documents, both only contain the string "Hello World".

The left document was created with Google Docs, the right one with "LaTeX".

Sure, the font is a bit different and the placement of the text content itself is also a little different, but that should be it, right?

No.

Once we look at the binary data of the document, it gets more and more confusing and the difference get bigger and bigger the more we look at the content.

So what's the deal?

Google Docs Document

LaTeX Document

As you can see we get already the first difference in the PDF file version number (the first line).

For Google's PDF we get PDF-1.4 and for the LaTeX doc it is PDF-1.5.

Due to the fact that PDF is by now an industry standard, the versions are also tagged with ISO numbers. The most recent PDF version (PDF 2.0) has the ISO ID ISO 32000-2:2020. And if you're curious about it, you can buy yourself a PDF version of the PDF version on iso.org (for just 221 CHF).

Kinda funny that you can buy a PDF document about the PDF format

Now if you look a little more into both generated documents, you will notice that albeit both spell "Hello World", none of them actually contain the combined letters spelling it out.

Further investigation

We can use UNIX tools to investigate this a little further.

In the following, the Google PDF is called test-doc-2.pdf and the LaTeX doc is called test-doc-3.pdf.

For instance pdfinfo gives us some information about the files.

First the Google Doc

> pdfinfo ./test-doc-2.pdf

Title: Untitled document

Producer: Skia/PDF m144 Google Docs Renderer

Custom Metadata: no

Metadata Stream: no

Tagged: yes

UserProperties: no

Suspects: no

Form: none

JavaScript: no

Pages: 1

Encrypted: no

Page size: 596 x 842 pts (A4)

Page rot: 0

File size: 11688 bytes

Optimized: no

PDF version: 1.4

And then the LaTeX doc

> pdfinfo ./test-doc-3.pdf

Creator: TeX

Producer: pdfTeX-1.40.27

CreationDate: Wed Nov 12 13:55:15 2025 CET

ModDate: Wed Nov 12 13:55:15 2025 CET

Custom Metadata: yes

Metadata Stream: no

Tagged: no

UserProperties: no

Suspects: no

Form: none

JavaScript: no

Pages: 1

Encrypted: no

Page size: 612 x 792 pts (letter)

Page rot: 0

File size: 13141 bytes

Optimized: yes

PDF version: 1.5

Using qpdf we can create a more readable PDF without object streams and compression

> qpdf -qdf --object-streams=disable ./test-doc-2.pdf ./test-doc-2.qdf.pdf

> qpdf -qdf --object-streams=disable ./test-doc-3.pdf ./test-doc-3.qdf.pdf

This produces the following two documents

Again, they look exactly the same inside the reader, but they're a bit more readable because nothing is compressed or streamed.

Once we look over the document's content, we can see blocks

BT

...

ET

which are our text boxes (BT: Begin Text, ET: End Text), and

begincmap

...

endcmap

which defines our character map for the document.

Doing some Python Kong-Fu allows us to read this data, and re-create the document content. It's not too trivial, but I'm sure you'll understand the gist of it.

We start with creating the character map

import re

def parse_to_unicode_cmap(cmap_text: str) -> dict[str, str]:

"""

Parse a single begincmap...endcmap text and return a dict mapping

keys like '<002b>' -> 'H'.

"""

cmap = {}

BF_RANGE_BLOCK = r"<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>\s+<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>\s+\[(.*?)\]"

FRANGE_BLOCK = r"<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>\s+<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>\s+<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>"

FRANGE = r"beginbfrange(.*?)endbfrange"

FCHAR = r"beginbfchar(.*?)endbfchar"

FCHAR_BLOCK = r"<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>\s+<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>"

# beginbfchar ... endbfchar

for bfchar_block in re.finditer(FCHAR, cmap_text, re.S | re.I):

block = bfchar_block.group(1)

for src, dst in re.findall(FCHAR_BLOCK, block):

key = f"<{int(src,16):04x}>" # normalized "<xxxx>"

cmap[key] = chr(int(dst, 16))

# beginbfrange ... endbfrange

for bfrange_block in re.finditer(FRANGE, cmap_text, re.S | re.I):

block = bfrange_block.group(1)

# three-hex form: <start> <end> <dst_start>

for start, end, dst in re.findall(FRANGE_BLOCK, block):

s, e, d = int(start, 16), int(end, 16), int(dst, 16)

for offset, codepoint in enumerate(range(s, e + 1)):

key = f"<{codepoint:04x}>"

cmap[key] = chr(d + offset)

# alternative bfrange form where destination is an array

# e.g. <start> <end> [ <dst1> <dst2> ... ]

for start, end, arr in re.findall(BF_RANGE_BLOCK, block, re.S):

s, e = int(start, 16), int(end, 16)

dsts = re.findall(r"<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>", arr)

for i, codepoint in enumerate(range(s, e + 1)):

if i < len(dsts):

key = f"<{codepoint:04x}>"

cmap[key] = chr(int(dsts[i], 16))

return cmapThe explanation is quite simple.

We have two major blocks we consider as definitions of our character map.

One is wrapped between beginfchar...endfchar, the other between beginbfrange...endbfrange.

FCHAR is a conversion pair with SOURCE and DESTINATION, e.g.

beginbfchar

<0000> <0049>

endbfcharThis maps for example the code <0000> to the character I.

The other block type bfrange contains 3 elements per record start, end, destination, e.g.

beginbfrange

<0000> <0010> <0049>

endbfrangeThis essentially maps the codes <0000>, <0001>, ..., <0010> to the character I.

Our method will iterate over every line of each block and create the character map based on these definitions.

One thing to mention, tho, if we have elements inside bfrange blocks that were present in the previous bfchar block we will overwrite them with the range content.

But we don't have immediately the character map content, rather the whole document.

With the following method we can extract the definition

def build_global_map_from_pdf_text(data: str) -> dict[str, str]:

maps = {}

for cmap_match in re.finditer(r"begincmap(.*?)endcmap", data, re.S | re.I):

mapping = parse_to_unicode_cmap(cmap_match.group(1))

# Later ones may override earlier ones for the same code — that's okay

maps.update(mapping)

return mapsProgressing further, apart from the character map we also need the text blocks. As previously mentioned, they're indicated by BT...ET blocks. We can yet again use our always helpful helper RegEx

def decode_bt_block(block_text: str, maps: dict[str, str]) -> str:

"""

Finds hex tokens <hhhh> inside the block and decodes using maps,

falling back to '?' when unknown.

"""

out = []

for m in re.finditer(r"<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>", block_text):

# hex representation with width 4 and prefixed 0

key = f"<{int(m.group(1), 16):04x}>"

out.append(maps.get(key, "?"))

return "".join(out)And finally wrapping up to just require the document binary data we can wrap everything into this neat little method

def extract_text_from_uncompressed_pdf(data: str) -> None:

maps = build_global_map_from_pdf_text(data)

content = []

for block in re.finditer(r"BT(.*?)ET", data, re.S):

decoded = decode_bt_block(block.group(1), maps)

# you may also want to print raw block for debugging

print(decoded)

content.append(decoded)

return contentFeel free to use one of the converted PDF files from earlier https://blog.godesteem.de/_includes/assets/2025-11-12/test-doc-2.qdf.pdf, e.g.

import requests

url = 'https://blog.godesteem.de/_includes/assets/2025-11-12/test-doc-2.qdf.pdf'

data = extract_text_from_uncompressed_pdf(requests.get(url, allow_redirects=True).content)and that will yield

Hello

WorldWoohoo, congrats! We managed to extract text content from our document(s)!

Alright, that's not fully usable for us, just yet. What we would actually want is apart from the text content also a form of structure, like bounding boxes or coordinates.

Structure Parsing

Thankfully, the PDF got us covered.

We can use the BT..ET blocks to retrieve this information.

Inside each block we have a set of instructions that help us structure the content.

These instructions include

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

Tm |

Set text matrix (scaling + rotation + initial position) |

Td |

Move text position (relative offset in text space) |

Td + Tj chain |

Position, draw text, move cursor |

TJ |

Basically like Td + Tj for a single element |

T* |

Move to next line |

Tf |

Set font and size (you can derive line height) |

Next in line would be recreating text sturcture, so apart from our text content, we also need to retrieve the position of each text element.

Note: That being said, the approach we're looking into here will only work well for documents that have horizontal text on the same line. Otherwise we will need to come up with a more sophisticated algorithm that will be beyond this post.

Great, now let's get started and extract coordinates for text!

First, we need to extend our extract_text_from_uncompressed_pdf method, to not only consider the BT..ET blocks, but also their prepending movement instruction that is indicated by the line ending cm. These blocks are page level coordinate transformations for all content that follows them.

This will allow us to extract all text content as well as create transformation matrices to move the content inside the document according to the structure defined inside the PDF.

def extract_text_from_uncompressed_pdf(data: str) -> list:

cmap = build_global_map_from_pdf_text(data)

CMD_RE = re.compile(

r"(\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+cm)" # 1: ...cm

r"|(BT(.*?)ET)", # 2: BT...ET

re.S

)

identity_matrix = [1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0]

ctm = list(identity_matrix) # Page-level Matrix

tm = list(identity_matrix) # Text Matrix

tlm = list(identity_matrix) # Text-Line Matrix

font = None

# just a default font size, will be extracted from the PDF

size = 12.0

all_text_items = []

for m in CMD_RE.finditer(data):

cm_match = m.group(1)

bt_content = m.group(3)

if cm_match:

ctm = [float(v) for v in cm_match.split()[:6]]

continue

if bt_content is None:

continue

try:

items, tm, tlm, size, font = decode_bt_block(

bt_content, cmap, ctm, tm, tlm, size, font

)

if items:

all_text_items.append(items)

except (ValueError, IndexError):

continue

return all_text_items

As you can see we're using a bit more advanced RegEx now. It essentially looks for two types of content First the lines ending with

...cm

second, the content wrapped inside BT..ET tags.

In our test document this could be

.75 0 0 .75 77.25 232.02759 cm

and

/F4 14.666667 Tf

1 0 0 -1 0 .47981739 Tm

88.774796 -13.2773438 Td <0049> Tj

4.0719757 0 Td <0052> Tj

8.1511078 0 Td <0051> Tj

8.1511078 0 Td <0057> Tj

We described the specific BT block attributes already in the table above.

The cm blocks contain 6 float values followed by a cm, basically like the Tm blocks inside BT blocks. But instead of a local transformation it contains a global one.

The first 4 values is the scaling matrix of the content

and the last two are the page coordinates to which to move

This allows us to compute coordinates simply by doing

Let's assume we have the starting coordinates [50, 20]

Great, this allows us now to properly extract bounding boxes of our text.

All we need to do is adjust our decode_bt_block method. Instead of strings, it will now return a list of structured elements with the form

{

"text": "Hello World",

"x": 0,

"y": 0,

"size": 12,

"bbox": [0, 0, 25.5, 12]

}This will be a bit more work now, because instead of just the reading all <hhhh> hex tokens, we now need to parse all different attributes to properly understand the structure.

For this we extend our simple Tj RegEx with definitions for Tm, Td, Tf and TJ

BT_CMD_RE = re.compile(

r"(\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+\S+\s+Tm)" # 1: Tm

r"|(\S+\s+\S+\s+Td)" # 2: Td

r"|(\S+\s+\S+\s+Tf)" # 3: Tf

r"|<([0-9A-Fa-f]+)>\s*Tj" # 4: Tj (simple)

r"|\[(.*?)\]\s*TJ" # 5: TJ (with positioning)

)This yields the following 6 groups

Tm: gives us 6 float valuesTd: 2 float valuesTf: 2 float valuesTj: hex token value (<hhhh>hex token without brackets ->hhhh)TJa list of elements, each are of form<hhhh> ... ...

For now and for the sake of simplicity we ignore the TJ blocks here, but you should definitely look into them!

def decode_bt_block(block_content: str, cmap: dict[str, str], ctm: list[float], tm: list[float], tlm: list[float], size: float, font_name: str = None):

items = []

local_tm = list(tm)

local_tlm = list(tlm)

local_size = size

local_font = font_name

for m in BT_CMD_RE.finditer(block_content):

...Because we're iterating over all BT..ET blocks, we need to keep track of the transformations. Hence, our method gets the global Page level, Text level and Text-Line level matrices as input.

Apart from that we pass the current font size and font name to the method, just for simplicities sake.

Like with the simple hex token extraction we iterate over the groups we find inside the provided text block.

Now, let's look inside this loop and see how we parse the content.

for m in BT_CMD_RE.finditer(block_content):

tm_match = m.group(1)

td_match = m.group(2)

tf_match = m.group(3)

tj_match = m.group(4)

TJ_match = m.group(5) # TODO: implement me

try:

if tm_match:

vals = [float(v) for v in tm_match.split()[:6]]

local_tm = vals

local_tlm = vals

elif td_match:

dx, dy = map(float, td_match.split()[:2])

move_matrix = [1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, dx, dy]

local_tlm = matrix_multiply(move_matrix, local_tlm)

local_tm = list(local_tlm)

elif tf_match:

parts = tf_match.split()

local_font = parts[0].strip("/")

local_size = float(parts[1])

elif tj_match:

hex_str = tj_match.lower()

for i in range(0, len(hex_str), 4):

code_hex = hex_str[i:i+4]

code = f"<{int(code_hex, 16):04x}>"

text = cmap.get(code, "?")

# This should use some more advanced heuristics

# to properly convert spacing

w_text_space = local_size

final_matrix = matrix_multiply(local_tm, ctm)

(tx, ty) = transform_point(0, 0, final_matrix)

w_page_simple = w_text_space * final_matrix[0]

h_page_simple = local_size * final_matrix[3]

bbox = (tx, ty, tx + w_page_simple, ty + h_page_simple)

items.append(dict(

text=text,

x=tx,

y=ty,

size=local_size * 0.5,

bbox=bbox

))

advance_matrix = [1, 0, 0, 1, w_text_space, 0]

local_tm = matrix_multiply(advance_matrix, local_tm)As you can see we're using two helper methods transform_point and matrix_multiply.

Those are quite literal just matrix-vector operators. I didn't want to integrate the next dependency, just to do some simple math.

Here are the two methods

def matrix_multiply(M1, M2):

"""Performs PDF matrix multiplication: M = M1 * M2"""

a1, b1, c1, d1, e1, f1 = M1

a2, b2, c2, d2, e2, f2 = M2

a = a1*a2 + b1*c2

b = a1*b2 + b1*d2

c = c1*a2 + d1*c2

d = c1*b2 + d1*d2

e = e1*a2 + f1*c2 + e2

f = e1*b2 + f1*d2 + f2

return [a, b, c, d, e, f]

def transform_point(x, y, M):

"""Transforms a point (x, y) by a matrix M."""

a, b, c, d, e, f = M

tx = x*a + y*c + e

ty = x*b + y*d + f

return tx, tyIt's simple rendering math. You have local coordinates of an object you want to render onto your screen. But your screen only knows global (world) coordinates. So to overcome this we "translate" the local matrix into world space, then compute new coordinates according to new world space. Just like we did in the example before.

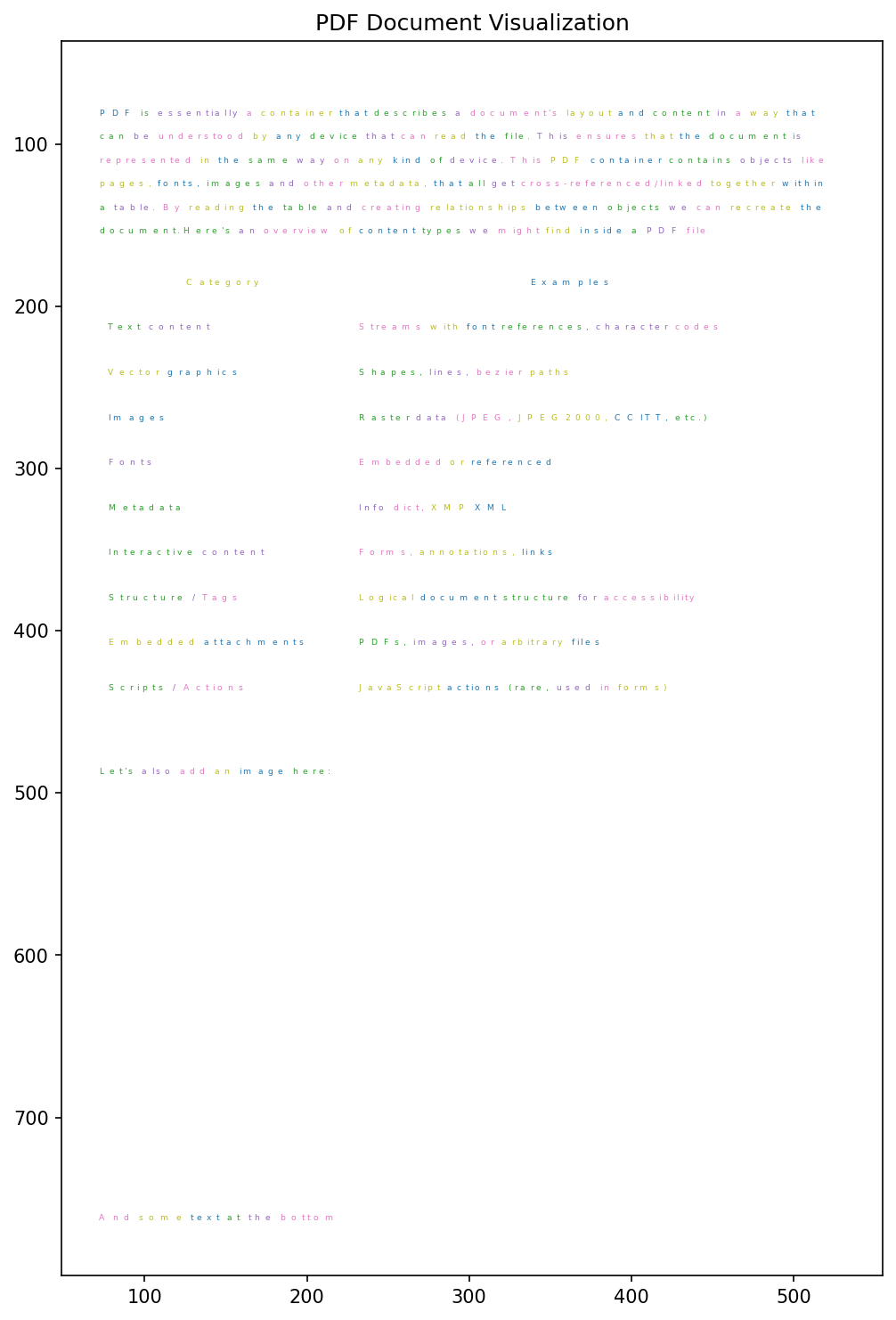

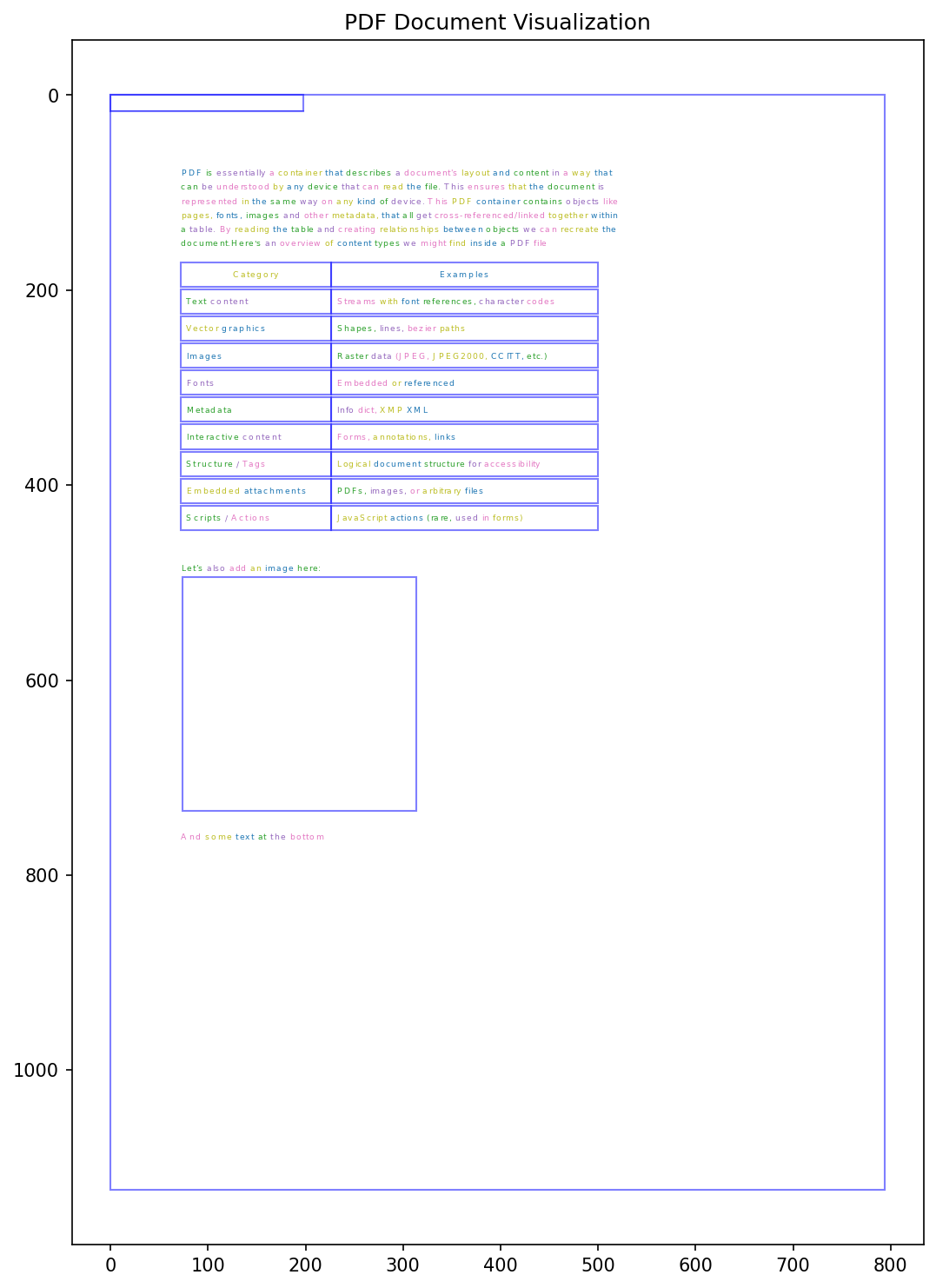

Let's consider a different doc that is a bit more complex.

Using this adjusted implementation we can now recreate the document structure as desired.

Vector Graphic Parsing

Vector graphics are quite similar to images, with the major difference of how they're encoded into the document. We differentiate between rect elements, which are rectangles and line elements which are just lines.

def find_vectors(data: str) -> list:

"""Finds simple rectangles and lines."""

vectors = []

for m in re.finditer(r"(\S+)\s+(\S+)\s+(\S+)\s+(\S+)\s+re", data):

x, y, w, h = map(float, m.groups())

vectors.append({

"type": "rect",

"bbox": [x, y, x + w, y + h]

})

for m in re.finditer(r"(\S+)\s+(\S+)\s+m\s+(\S+)\s+(\S+)\s+l\s+S", data):

x1, y1, x2, y2 = map(float, m.groups())

vectors.append({

"type": "line",

"p1": [x1, y1],

"p2": [x2, y2]

})

return vectorsThis helps us drastically to identify tables, as well as images inside PDFs.

As you can see we can already identify all elements on the page. The outer bounding box represents the full document, the lines and columns in the middle of the page represent the table and the box overlapping with the documents center we have the image.

Great, this gives us an amazing base to start off. But unfortunately, things get harder and harder from here on.

Our full script is getting bigger and bigger and accumulates more and more dependencies.

Considering this, and the fact that we currently still need to decompress the incoming PDF files as initially mentioned using qpdf, we will now pivot to a more robust solution.

Putting things together

Supporting existing solutions

There's not yet a single library that claims to do exactly what we're doing here.

Hence, we still need to put in some effort to end up with a solid solution.

A brief research on the most commonly used libraries concluded that we should probably use one of these:

- PyMuPDF: a high performance Python library for data extraction, analysis, conversion & manipulation of PDF (and other) documents

- pdfplumber: Plumb a PDF for detailed information about each char, rectangle, line, et cetera — and easily extract text and tables

- Unstructured: Convert documents to structured data effortlessly. Unstructured is open-source ETL solution for transforming complex documents into clean, structured formats for language models. Visit our website to learn more about our enterprise grade Platform product for production grade workflows, partitioning, enrichments, chunking and embedding.

| Feature | PyMuPDF (fitz) | pdfplumber | Unstructured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text Extraction | Excellent (C-Speed, Dict/JSON output) | Excellent (Visual/Layout preservation) | Good (OCR/Partitioning) |

| Table Extraction | Good (Fast, Heuristic) | Excellent (Configurable, Visual Debug) | Good (Auto-detection) |

| Vector Graphics | Full Support (Paths to SVG) | Limited (Lines/Rects only) | Limited (Rasterizes) |

| Raster Images | Native Extraction | Native Extraction | Native (OCR capable) |

| Output Format | Dict, JSON, XML, Markdown | JSON/CSV export | JSON (Element list) |

| Execution Speed | 🚀 Very Fast (~0.1s/page) | 🐢 Slow (~1-5s/page) | 🐢 Slow (~1.5s+/page) |

| License | AGPL (Restrictive) / Commercial | MIT (Permissive) | Apache 2.0 (Permissive) |

We decided for now to go with PyMuPDF due to its performance.

Implementation plan

To reduce the number of calls we do to the library we will split the process into multiple steps, sharing results between them.

- Extract raw PDF structure, incl. Images and Vector Graphics

- Detect Text lines based on structure

- Detect Text columns based on Text Lines and structure (for tables)

- Detect tables based on text columns

- Detect text paragraphs

- Convert structure into easy to digest format for LLMs

Only the first step uses PyMuPDF's fitz, everything past this step is using lightweight algorithms.

Focusing on text only extraction our first step looks similar to this:

def extract_structure(pdf_file):

doc = fitz.open(pdf_file)

structure: Dict[str, Any] = {"path": pdf_file, "pages": [], "page_count": len(doc)}

imgs = []

mat = fitz.Matrix(0.5, 0.5)

for pno, page in enumerate(doc):

pix = page.get_pixmap(matrix=mat)

imgs.append(pix.pil_image())

page_w, page_h = page.rect.width, page.rect.height

page_dict = {"page_number": pno + 1, "width": page_w, "height": page_h, "text": [], "images": [], "vectors": []}

tdict = page.get_text("dict")

for block in tdict.get("blocks", []):

if block.get("type") == 0: # text

for line in block.get("lines", []):

for span in line.get("spans", []):

txt = span.get("text", "")

if not txt.strip(): continue

bbox = [round(v, 2) for v in span.get("bbox", [])]

txt = normalize_text(txt)

page_dict["text"].append({

"text": txt, "bbox": bbox, "font": span.get("font"),

"size": span.get("size"), "flags": span.get("flags"),

"x0": bbox[0], "y0": bbox[1], "x1": bbox[2], "y1": bbox[3],

"cx": (bbox[0] + bbox[2]) / 2.0, "cy": (bbox[1] + bbox[3]) / 2.0,

})

structure['pages'].append(page_dict)

return structure, imgsFrom reading the code you will notice that we return two variables here, the first one is the PDF's structure, the second one a list of image objects, for each page one.

The structure we receive back contains information about the source file as well as the content that we were able to extract from the PDF file. For every page we receive an individual object that holds an array of text, images and vector graphics that are used within the specific page.

Each text entry is another object that contains coordinates where the text is found on the page, as well as font information and the written text.

{

"text": "The line of text",

"bbox": [0, 120, 0, 15],

"font": "Arial",

"size": 10,

"flags": "",

"x0": 0,

"y0": 0,

"x1": 120,

"y1": 15,

"cx": 60.0,

"cy": 7.5

}The page's text entities aren't sorted yet. All we have is individual text chunks that we now need to structrue again.

structure, page_imgs = extract_structure('some_file.pdf')

text_spans = structure['pages'][0]['text']We use this structure, or specifically the text spans within the page structures, to detect lines within the document.

For each detection step we're building a "Detector". Each detector implements a detect method that receives a set of extracted structure elements.

For instance the LineDetector, which is used to identify lines of text from given text spans

class LineDetector:

def detect(self, spans: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

if not spans: return []

sorted_spans = sorted(spans, key=lambda s: (s["y0"], s["x0"]))

lines: List[Dict[str, Any]] = []

heights = [s["y1"] - s["y0"] for s in spans if s["y1"] - s["y0"] > 0]

median_height = float(np.median(heights)) if heights else 10.0

line_threshold = max(2.0, median_height * 0.4)

current_line_spans = [sorted_spans[0]]

for i in range(1, len(sorted_spans)):

prev_s, curr_s = current_line_spans[-1], sorted_spans[i]

if abs(curr_s["cy"] - prev_s["cy"]) <= line_threshold:

current_line_spans.append(curr_s)

else:

all_x0, all_y0 = [s['x0'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y0'] for s in current_line_spans]

all_x1, all_y1 = [s['x1'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y1'] for s in current_line_spans]

bbox = [min(all_x0), min(all_y0), max(all_x1), max(all_y1)]

lines.append({

"spans": current_line_spans,

"text": " ".join(s['text'] for s in sorted(current_line_spans, key=lambda s: s['x0'])),

"bbox": bbox, "x0": bbox[0], "y0": bbox[1], "x1": bbox[2], "y1": bbox[3],

"cx": (bbox[0] + bbox[2]) / 2, "cy": (bbox[1] + bbox[3]) / 2,

})

current_line_spans = [curr_s]

if not current_line_spans:

return lines

all_x0, all_y0 = [s['x0'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y0'] for s in current_line_spans]

all_x1, all_y1 = [s['x1'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y1'] for s in current_line_spans]

bbox = [min(all_x0), min(all_y0), max(all_x1), max(all_y1)]

lines.append({

"spans": current_line_spans,

"text": " ".join(s['text'] for s in sorted(current_line_spans, key=lambda s: s['x0'])),

"bbox": bbox, "x0": bbox[0], "y0": bbox[1], "x1": bbox[2], "y1": bbox[3],

"cx": (bbox[0] + bbox[2]) / 2, "cy": (bbox[1] + bbox[3]) / 2,

})

return linesThis merges text that is aligned on the same horizontal line based on coordinates within the extracted text spans based on their x0 values. Which will yield lines of text.

LineDetector().detect(text_spans)This covers 1. (text only) and 2.. For the remaining detection steps we implemented the detectors TableDetector and ColumnDetector and extended our original structure extraction method with the logic for images and vector graphics.

Transforming the structure

Once the full structure is extracted we need to transform it into a format (7.) that can be easily used by Large Language Models like Gemma.

This is rather a boring excercise. What we basically do is convert any structure into valid Markdown, if possible and create bits of information that are easier to digest by the model.

The main point to state here is that we transform tables into a nice markdown structure and remove unnecessary content/bloat from our JSON structure.

Wrapping up

For the final solution we need to install the following dependencies:

fitz(aka.PyMuPDF)scikit-learnPillownumpy

You can find the full pre-processing implementation here:

Full implementation

Implementation PDFParser

import fitz

import re

from sklearn.cluster import AgglomerativeClustering

from typing import List, Dict, Any

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

def unescape_text(text):

"""

Converts literal unicode escape sequences (like \\u0130) into actual characters (İ).

This fixes issues where LLMs output escaped JSON strings.

"""

# Pattern to match literal \\u followed by 4 hex digits (e.g. \\u0130)

pattern = r'\\u([0-9a-fA-F]{4})'

def replace_match(match):

try:

return chr(int(match.group(1), 16))

except ValueError:

return match.group(0)

return re.sub(pattern, replace_match, str(text))

def normalize_text(text):

"""

Robust normalization:

1. Unescape unicode characters (fix \\uXXXX artifacts)

2. Strip whitespace

3. Lowercase

4. Collapse multiple spaces

"""

# Step 1: Fix broken unicode (e.g. "EYYUB\\u0130" -> "EYYUBİ")

clean = unescape_text(text)

# Step 2: Standard normalization

return re.sub(r'\s+', ' ', clean).strip()

def group_lines_to_paragraphs(lines: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> List[List[Dict[str, Any]]]:

if not lines: return []

sorted_lines = sorted(lines, key=lambda l: l["y0"])

heights = [l["y1"] - l["y0"] for l in sorted_lines if l["y1"] - l["y0"] > 0]

if not heights: return []

median_height = float(np.median(heights))

gap_threshold = median_height * 0.6

paragraphs: List[List[Dict[str, Any]]] = []

current_para: List[Dict[str, Any]] = [sorted_lines[0]]

for i in range(1, len(sorted_lines)):

prev_ln, curr_ln = sorted_lines[i-1], sorted_lines[i]

gap = curr_ln["y0"] - prev_ln["y1"]

prev_end_char = prev_ln["text"].strip()[-1] if prev_ln["text"].strip() else ""

is_punct_break = prev_end_char in {".", "!", "?", ":"} and gap > (median_height * 0.2)

if gap > gap_threshold or is_punct_break:

paragraphs.append(current_para)

current_para = [curr_ln]

else:

current_para.append(curr_ln)

if current_para: paragraphs.append(current_para)

return paragraphs

class LineDetector:

def detect(self, spans: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

if not spans: return []

sorted_spans = sorted(spans, key=lambda s: (s["y0"], s["x0"]))

lines: List[Dict[str, Any]] = []

heights = [s["y1"] - s["y0"] for s in spans if s["y1"] - s["y0"] > 0]

median_height = float(np.median(heights)) if heights else 10.0

line_threshold = max(2.0, median_height * 0.4)

current_line_spans = [sorted_spans[0]]

for i in range(1, len(sorted_spans)):

prev_s, curr_s = current_line_spans[-1], sorted_spans[i]

if abs(curr_s["cy"] - prev_s["cy"]) <= line_threshold:

current_line_spans.append(curr_s)

else:

all_x0, all_y0 = [s['x0'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y0'] for s in current_line_spans]

all_x1, all_y1 = [s['x1'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y1'] for s in current_line_spans]

bbox = [min(all_x0), min(all_y0), max(all_x1), max(all_y1)]

lines.append({

"spans": current_line_spans,

"text": " ".join(s['text'] for s in sorted(current_line_spans, key=lambda s: s['x0'])),

"bbox": bbox, "x0": bbox[0], "y0": bbox[1], "x1": bbox[2], "y1": bbox[3],

"cx": (bbox[0] + bbox[2]) / 2, "cy": (bbox[1] + bbox[3]) / 2,

})

current_line_spans = [curr_s]

if current_line_spans:

all_x0, all_y0 = [s['x0'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y0'] for s in current_line_spans]

all_x1, all_y1 = [s['x1'] for s in current_line_spans], [s['y1'] for s in current_line_spans]

bbox = [min(all_x0), min(all_y0), max(all_x1), max(all_y1)]

lines.append({

"spans": current_line_spans,

"text": " ".join(s['text'] for s in sorted(current_line_spans, key=lambda s: s['x0'])),

"bbox": bbox, "x0": bbox[0], "y0": bbox[1], "x1": bbox[2], "y1": bbox[3],

"cx": (bbox[0] + bbox[2]) / 2, "cy": (bbox[1] + bbox[3]) / 2,

})

return lines

class ColumnDetector:

def detect(self, spans: List[Dict[str, Any]], max_columns: int = 4, gap_threshold: float | None = None) -> List[int]:

if not spans: return []

centers = np.array([s["cx"] for s in spans]).reshape(-1, 1)

if gap_threshold is None:

widths = np.array([s["x1"] - s["x0"] for s in spans])

median_w = np.median(widths) if widths.size else 50

gap_threshold = max(30.0, median_w * 0.6)

clustering = AgglomerativeClustering(n_clusters=None, distance_threshold=gap_threshold, linkage="ward")

labels = clustering.fit_predict(centers)

unique_labels, means = np.unique(labels, return_counts=False), [np.mean(centers[labels == l]) for l in np.unique(labels)]

sorted_labels = [label for _, label in sorted(zip(means, unique_labels))]

label_to_col = {label: idx for idx, label in enumerate(sorted_labels)}

cols = [min(label_to_col[l], max_columns - 1) for l in labels]

return cols

class TableDetector:

def detect(self, lines: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

"""

Detects tables by finding consecutive lines that have multiple segments

which vertically align with each other.

"""

if len(lines) < 2:

return []

# 1. Analyze every line to see if it has "columns" (segments)

# We use a looser threshold (1.5 spaces) to catch tight tables

line_structures = []

for ln in lines:

segs = self.get_line_segments(ln, space_scale=1.5)

line_structures.append({

"line_obj": ln,

"segments": segs,

"is_multi_col": len(segs) > 1

})

tables = []

current_table_lines = []

# 2. Group consecutive lines that look like they belong to the same grid

for i in range(len(line_structures)):

curr = line_structures[i]

prev = line_structures[i-1] if i > 0 else None

is_table_part = False

if curr["is_multi_col"]:

# If it has columns, check if it aligns with the previous table line

if current_table_lines:

prev_table_line = current_table_lines[-1]

# Check alignment: Do at least 50% of segments align with the previous line?

matches = 0

for c_seg in curr["segments"]:

for p_seg in prev_table_line["segments"]:

if self.segments_overlap(c_seg, p_seg):

matches += 1

break

if matches > 0:

is_table_part = True

else:

# Start of a potential table

# Heuristic: Must be followed by another multi-col line to be a table

if i + 1 < len(line_structures):

next_ln = line_structures[i+1]

if next_ln["is_multi_col"]:

# Check alignment with next

matches = 0

for c_seg in curr["segments"]:

for n_seg in next_ln["segments"]:

if self.segments_overlap(c_seg, n_seg):

matches += 1

break

if matches > 0:

is_table_part = True

# 3. Handle Vertical Isolation (Whitespace heuristic)

# If we have a table going, allows single-column lines if they are "sandwiched" closely

if not is_table_part and current_table_lines:

# Allow a single line break or a header line inside a table

# if the vertical gap is small

gap = curr["line_obj"]["y0"] - current_table_lines[-1]["line_obj"]["y1"]

if gap < 15.0: # Small vertical gap threshold

# It might be a wrapped row.

# (Simplification: for now, strict visual alignment is safer)

pass

if is_table_part:

current_table_lines.append(curr)

else:

if len(current_table_lines) >= 2:

tables.append(self.process_table_block(current_table_lines))

current_table_lines = []

# Catch trailing table

if len(current_table_lines) >= 2:

tables.append(self.process_table_block(current_table_lines))

return tables

def process_table_block(self, block_structs: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> Dict[str, Any]:

"""

Converts a list of raw line structures into a clean table dictionary.

Recalculates columns based on the aggregate of all lines in the block.

"""

# 1. Collect all x-intervals from all lines

all_segments = []

for item in block_structs:

all_segments.extend(item["segments"])

# 2. Determine global column boundaries for this block using X-clustering

# (We reuse the logic from the old script here but restricted to this block)

if not all_segments: return {}

xs = np.array([(s["x0"] + s["x1"])/2 for s in all_segments]).reshape(-1, 1)

# Cluster centers to find column buckets

clustering = AgglomerativeClustering(n_clusters=None, distance_threshold=20, linkage="ward")

labels = clustering.fit_predict(xs)

# Map unique labels to sorted x-positions

unique_labels = np.unique(labels)

col_centers = []

for l in unique_labels:

center = np.mean(xs[labels == l])

col_centers.append((l, center))

col_centers.sort(key=lambda x: x[1])

label_map = {l: i for i, (l, c) in enumerate(col_centers)}

num_cols = len(unique_labels)

# 3. Build the grid

rows = []

for item in block_structs:

row_cells = [""] * num_cols

for seg in item["segments"]:

# Find which column this segment belongs to

seg_cx = (seg["x0"] + seg["x1"]) / 2

# Find closest column center (naive but effective given the clustering)

closest_lbl = min(unique_labels, key=lambda l: abs(np.mean(xs[labels==l]) - seg_cx))

col_idx = label_map[closest_lbl]

# Append text (handle overlaps)

current_text = row_cells[col_idx]

row_cells[col_idx] = (current_text + " " + seg["text"]).strip()

rows.append(list(filter(bool, row_cells)))

# 4. Calculate BBox

all_x0 = [l["line_obj"]["x0"] for l in block_structs]

all_y0 = [l["line_obj"]["y0"] for l in block_structs]

all_x1 = [l["line_obj"]["x1"] for l in block_structs]

all_y1 = [l["line_obj"]["y1"] for l in block_structs]

bbox = [min(all_x0), min(all_y0), max(all_x1), max(all_y1)]

return {"rows": rows, "bbox": [round(v, 2) for v in bbox]}

@staticmethod

def segments_overlap(seg1: Dict[str, Any], seg2: Dict[str, Any], tolerance: float = 5.0) -> bool:

"""Checks if two segments vertically align (share x-coordinates)."""

return max(0, min(seg1["x1"], seg2["x1"]) - max(seg1["x0"], seg2["x0"])) > tolerance

def get_line_segments(self, line: Dict[str, Any], space_scale: float = 2.0) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

"""

Breaks a line into visual segments based on horizontal gaps.

User Heuristic: Gap > space character.

"""

spans = sorted(line["spans"], key=lambda s: s["x0"])

if not spans:

return []

# Calculate an approximate space width for this specific line based on font size

# Average char width is roughly height / 2. A wide gap is ~ 2 to 3 spaces.

avg_font_size = np.mean([s["size"] for s in spans]) if spans else 10.0

gap_threshold = avg_font_size * 0.6 * space_scale

segments = []

current_segment = [spans[0]]

for i in range(1, len(spans)):

prev = spans[i-1]

curr = spans[i]

gap = curr["x0"] - prev["x1"]

if gap > gap_threshold:

# Gap detected: close current segment and start new

segments.append(current_segment)

current_segment = [curr]

else:

current_segment.append(curr)

segments.append(current_segment)

# Convert list of spans into simplified segment dicts

segment_dicts = []

for seg in segments:

x0 = min(s["x0"] for s in seg)

x1 = max(s["x1"] for s in seg)

text = " ".join(s["text"] for s in seg)

segment_dicts.append({"x0": x0, "x1": x1, "text": text, "spans": seg})

return segment_dicts

class PDFParser:

def __init__(self, pdf_file: str | bytes):

self.pdf_file = pdf_file

self.table_detector = TableDetector()

self.line_detector = LineDetector()

self.column_detector = ColumnDetector()

def create_structure(self) -> Dict[str, Any]:

struct, imgs = self.extract_pdf_structure()

for page in struct.get("pages", []):

spans = page.get("text", [])

if not spans: continue

lines = self.line_detector.detect(spans)

col_labels = self.column_detector.detect(spans)

for s, c in zip(spans, col_labels): s["col"] = int(c)

for ln in lines:

span_cols = [sp.get("col", 0) for sp in ln.get("spans", [])]

ln["col"] = int(max(set(span_cols), key=span_cols.count)) if span_cols else 0

page["lines"] = lines

# Detect tables FIRST

page["tables"] = self.table_detector.detect(lines)

# Exclude table lines from paragraph analysis

table_line_indices = set()

for tbl in page['tables']:

bx0, by0, bx1, by1 = tbl.get("bbox", [0, 0, 0, 0])

for i, ln in enumerate(lines):

if (by0 <= ln['cy'] <= by1) and (max(bx0, ln['x0']) < min(bx1, ln['x1'])):

table_line_indices.add(i)

non_table_lines = [ln for i, ln in enumerate(lines) if i not in table_line_indices]

# Group remaining lines into paragraphs per column

paragraphs_by_col: Dict[int, List[List[Dict[str, Any]]]] = {}

cols = sorted(list(set(ln.get("col", 0) for ln in non_table_lines)))

for col_id in cols:

col_lines = [ln for ln in non_table_lines if ln.get("col", 0) == col_id]

if col_lines:

paragraphs_by_col[col_id] = group_lines_to_paragraphs(col_lines)

page["paragraphs_by_col"] = paragraphs_by_col

return struct, imgs

def extract_pdf_structure(self) -> Dict[str, Any]:

structure: Dict[str, Any] = {"path": self.pdf_file if isinstance(self.pdf_file, str) else '', "pages": []}

try:

doc = fitz.open(self.pdf_file)

except Exception as e:

try:

doc = fitz.open('pdf', self.pdf_file)

except Exception as ex:

raise RuntimeError(f"Failed to open PDF '{self.pdf_file}': {ex}")

structure["page_count"] = len(doc)

imgs = []

mat = fitz.Matrix(0.5, 0.5)

for pno, page in enumerate(doc):

pix = page.get_pixmap(matrix=mat)

imgs.append(pix.pil_image())

page_w, page_h = page.rect.width, page.rect.height

page_dict = {"page_number": pno + 1, "width": page_w, "height": page_h, "text": [], "images": [], "vectors": []}

try:

tdict = page.get_text("dict")

for block in tdict.get("blocks", []):

if block.get("type") == 0: # text

for line in block.get("lines", []):

for span in line.get("spans", []):

txt = span.get("text", "")

if not txt.strip(): continue

bbox = [round(v, 2) for v in span.get("bbox", [])]

txt = normalize_text(txt)

page_dict["text"].append({

"text": txt, "bbox": bbox, "font": span.get("font"),

"size": span.get("size"), "flags": span.get("flags"),

"x0": bbox[0], "y0": bbox[1], "x1": bbox[2], "y1": bbox[3],

"cx": (bbox[0] + bbox[2]) / 2.0, "cy": (bbox[1] + bbox[3]) / 2.0,

})

except Exception as e:

print(f"[warn] text extraction failed on page {pno+1}: {e}")

try:

img_idx = 0

for img in page.get_images(full=True):

xref = img[0]

try:

base = doc.extract_image(xref)

img_bytes, img_ext = base["image"], base.get("ext", "png")

img_bbox = page.get_image_bbox(img).irect

page_dict["images"].append({

"bbox": [img_bbox.x0, img_bbox.y0, img_bbox.x1, img_bbox.y1],

"xref": xref,

"ext": img_ext,

"width": base.get("width"), "height": base.get("height")

})

img_idx += 1

except Exception as e:

print(f"[warn] could not extract image xref {xref} on page {pno+1}: {e}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"[warn] image extraction failed on page {pno+1}: {e}")

try:

for d in page.get_drawings():

r = d.get("rect")

if r:

bbox = [round(r.x0, 2), round(r.y0, 2), round(r.x1, 2), round(r.y1, 2)]

page_dict["vectors"].append({"type": "rect", "bbox": bbox, "width": d.get("width")})

except Exception:

pass

structure["pages"].append(page_dict)

doc.close()

return structure, imgsImplementation StructureCreator

import json

class StructureCreator:

def transform(self, input_data):

"""

Transforms raw PDF JSON into a clean, grounded structure for Vision LLMs.

"""

# If input is a string, parse it; otherwise assume it's a dict

if isinstance(input_data, str):

data = json.loads(input_data)

else:

data = input_data

transformed_doc = {

"filename": data.get("path", "unknown_file"),

"total_pages": len(data.get("pages", [])),

"pages": []

}

for page in data.get("pages", []):

page_width = page.get("width")

page_height = page.get("height")

structured_page = {

"page_number": page.get("page_number"),

"dimensions": [int(page_width), int(page_height)],

"content": []

}

# 1. Process Tables (High Priority for grounding)

# We define tables first so we can potentially filter out text that exists inside tables

# to avoid duplication (optional, but recommended).

table_bboxes = []

for table in page.get("tables", []):

bbox = [int(n) for n in table.get("bbox", [0,0,0,0])]

table_bboxes.append(bbox)

# Convert table rows to Markdown format

md_table = self._json_rows_to_markdown(table.get("rows", []))

structured_page["content"].append({

"type": "table",

"bbox": bbox,

"format": "markdown",

"data": md_table

})

# 2. Process Images

for img in page.get("images", []):

structured_page["content"].append({

"type": "image",

"bbox": [int(n) for n in img.get("bbox", [0,0,0,0])],

"source_filename": img.get("filename", "embedded")

})

# 3. Process Text Lines

# We prefer 'lines' over 'text' spans because they are pre-assembled.

for line in page.get("lines", []):

line_bbox = [int(n) for n in line.get("bbox", [0,0,0,0])]

# Simple collision detection: If this text line is inside a table we already processed,

# we might want to skip it to reduce noise.

# (Logic: Center point of line is inside a table bbox)

cx = line.get("cx", line_bbox[0])

cy = line.get("cy", line_bbox[1])

is_inside_table = False

for t_box in table_bboxes:

if (t_box[0] <= cx <= t_box[2]) and (t_box[1] <= cy <= t_box[3]):

is_inside_table = True

break

if not is_inside_table:

structured_page["content"].append({

"type": "text",

"bbox": line_bbox,

"text": line.get("text", "").strip()

})

structured_page['content'] = sorted(

structured_page['content'],

key=lambda x: x['bbox'][1]

)

transformed_doc["pages"].append(structured_page)

return transformed_doc

def _json_rows_to_markdown(self, rows):

"""Helper to convert list of lists into a Markdown table string."""

if not rows:

return ""

try:

# headers are usually the first row

headers = rows[0]

# Determine if headers are valid strings

clean_headers = [str(h).replace("\n", " ") for h in headers]

md_lines = []

# Header row

md_lines.append("| " + " | ".join(clean_headers) + " |")

# Separator row

md_lines.append("| " + " | ".join(["---"] * len(headers)) + " |")

# Body rows

for row in rows[1:]:

clean_row = [str(cell).replace("\n", " ") if cell is not None else "" for cell in row]

md_lines.append("| " + " | ".join(clean_row) + " |")

return "\n".join(md_lines)

except Exception:

return "Error generating table content"During inference we first use the PDFParser, then the StructureCreator to build the payload that is then being wrapped into a prompt dedicated for the document.

For example for a running instance of llama.cpp's server

import requests

import base64

from io import BytesIO

# from ... import PDFParser

# from ... import StructureCreator

def convert_pdf(self, file_content):

parser = PDFParser(file_content)

res, pdf_pages = parser.create_structure()

creator = StructureCreator()

final = creator.transform(res)

user_content = []

for img in pdf_pages:

buffered = BytesIO()

img.save(buffered, format='jpeg')

base64_image = base64.b64encode(buffered.getvalue()).decode('utf-8')

user_content.append({

"type": "image_url",

"image_url": {

"url": f"data:image/jpeg;base64,{base64_image}"

}

})

return final, user_content

structure, images = convert_pdf('mypdf.pdf')

llama_cpp_host = 'http://localhost:8080/v1/chat/completions'

res = requests.post(

llama_cpp_host,

json={

'messages': images + [

{

'role': 'user',

'content': [

{

'type': 'text',

'text': f'Transcribe the full document based on this structure definition: {json.dumps(structure)}'

}

]

}

]

}

)

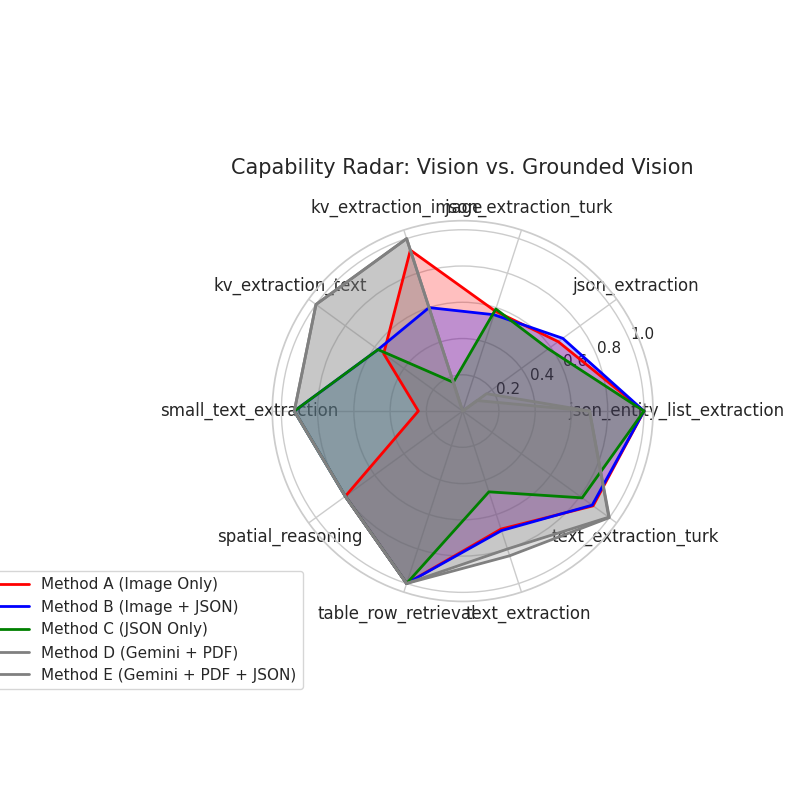

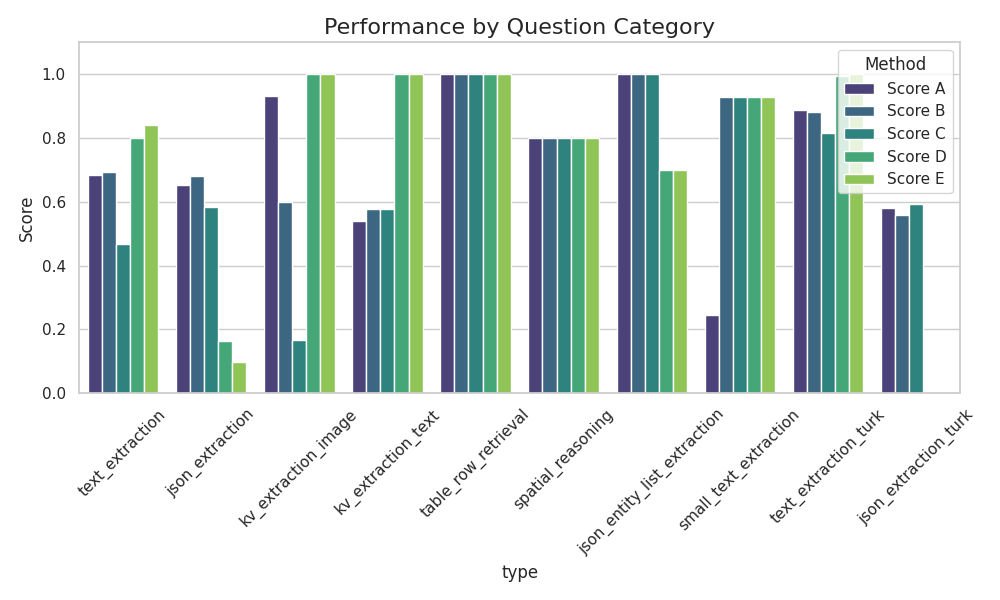

print(res.json()['choices'][0]['messages']['content'])This should yield more reliable results than just using image data. We also ran a small set of experimental benchmarks.

You can see the results below, underneath you will find a legend for the charts.

| Method name | Description |

|---|---|

| Method A | Gemma with Image input |

| Method B | Gemma with Image and Structure input |

| Method C | Gemma with Structure input |

| Method D | Gemini with native PDF |

| Method E | Gemini with native PDF and JSON |

Conclusion

Since my first self rendered LaTeX document I wanted to dig deeper into the domain of PDFs. With this post I finally managed to do so.

We looked into simple elements contained inside a PDF, learned about compression and streaming a little and got our hands dirty by reading de-compressed files manually.

Once we had a better understanding of the meta data inside PDFs we pivoted to the implementation state. Due to the fact that explanations would be cumbersome and boring and dry we wrapped up things quickly, but still provided the final implementation of readers to play around with.

For the future and to move forward with the implementation I would suggest to look deeper into table parsing.

Apart from that, this approach currently only works with correct PDF documents. No further analysis is performed on embedded graphics (vector or image). To accelerate the performance of LLMs with vision capabilities I would suggest using a model like DocLing or any other vision LLM that can produce document structure.